Weaving, Trying to Make Sense of my Time at the Bottom of this Planet, Occasionally Tending our Sisyphaen Patch

by the Goddess of Procrastination and Expert Forgetter

2006/12/30

How to Prepare Your Loom - A Short Version

I just found this post by Cathy in Maryland. It's a much more concise lesson on how a loom is prepared.

2006/12/26

Baker's Apprentice

Several things happened since June. But before I get into it, let me say I am not placing myself above other weavers, that I do not see myself any better. What I am trying to do is to have a conceptual direction for my art, or if you like, I'm trying to have a clearer product positioning; these two statements sound so different, and yet in my mind, for now, I understand them to be remarkably similar.

In early July, I had a One-on-One with Martin at Arts Marketing. The crux of the discussion was, I may be a different kind of a weaver in that I aspire to weave textiles outside of what is commonly expected of handweavers in New Zealand or Nelson, at least for now. He told me to build stronger ties with weavers with similar aspirations, and to seek inspiration from artists in other disciplines as well.

In October, Randall Darwall told me to be my own apprentice.

Later in October, I met Sue Broad, who now lives in Nelson, and with her arrival, I have, for the first time, a warm-blooded (as opposed to mostly-over-the-Internet) weaving buddy I can talk to and have coffee with and admire each other's stash with. I also became friends with song-writer Kath Bee at a time when we are both taking baby-steps and giant leaps into our respective worlds.

A couple of weeks ago, sculptor Tim Wraight and designer Claudia Lacher, both of whom I met at the June Retreat, came over. While discussing my transformation into a weaver and search for an identity, Tim recalled when he finished his apprenticeship and was about to go solo. He declared he would not trouble himself with "bread and butter" minutiae, but would make cake only, and that I should do the same.

So, in 2007, I'm going to be an apprentice baker who aspires to bakes only the moistest, most delicate, and the most delicious cakes. And if this isn't a clear enough direction, I have no business in art.

Liz, Angel Food, Devil's Food, orange, or whatever, you and I have lots of cakes to go through in our respective lives; I hope we get to share some in person.

In early July, I had a One-on-One with Martin at Arts Marketing. The crux of the discussion was, I may be a different kind of a weaver in that I aspire to weave textiles outside of what is commonly expected of handweavers in New Zealand or Nelson, at least for now. He told me to build stronger ties with weavers with similar aspirations, and to seek inspiration from artists in other disciplines as well.

In October, Randall Darwall told me to be my own apprentice.

Later in October, I met Sue Broad, who now lives in Nelson, and with her arrival, I have, for the first time, a warm-blooded (as opposed to mostly-over-the-Internet) weaving buddy I can talk to and have coffee with and admire each other's stash with. I also became friends with song-writer Kath Bee at a time when we are both taking baby-steps and giant leaps into our respective worlds.

A couple of weeks ago, sculptor Tim Wraight and designer Claudia Lacher, both of whom I met at the June Retreat, came over. While discussing my transformation into a weaver and search for an identity, Tim recalled when he finished his apprenticeship and was about to go solo. He declared he would not trouble himself with "bread and butter" minutiae, but would make cake only, and that I should do the same.

So, in 2007, I'm going to be an apprentice baker who aspires to bakes only the moistest, most delicate, and the most delicious cakes. And if this isn't a clear enough direction, I have no business in art.

Liz, Angel Food, Devil's Food, orange, or whatever, you and I have lots of cakes to go through in our respective lives; I hope we get to share some in person.

Artist/Craftsperson Continuum

Then in June, I went to a weekend Artists Retreat organized by Martin at Arts Marketing. It was designed for artists to learn how to market art (from paintings to woodwork to performances to novels) and to meet other artists.

While working on the previous post, I got used to thinking of myself as an artists whose discipline is textiles; handweaving to be precise. In spite of the superbly organized Retreat, and making new friends, I came home feeling defeated because I felt a chasm between pure art (the kind you can't use) and applied art/craft (things with utility and beauty). I was not sure where I was heading, and I wasn't sure where my textiles fitted in the scheme of things.

The title comes from a chart I made in 2000 which shows pure artist (who may use fiber) at one end, and cottage-industry-production-weaver at the other, and pin-pointing where I wanted to be; it is my visual mission statement.

ARTIST/CRAFTSPERSON CONTINUUM

Drafted June 2006

I was very happy being an artist last week; I want to weave artistic, unique pieces of shawls, scarves and yardage that are wonderful to the touch, beautiful to look at, but are hard wearing serious textiles. But of course the story didn't end there.

For the first forty years of my life, I believed, "of course the glass is half full, and look, if you bend your knees this way, it looks more like 3/4 full!" But of late, I not only see that it's half-empty, but in certain lights, I looks completely empty. This week, it's not just empty, the glass is dirty!

I attended an Artists Retreat at St Arnaud this past weekend; it was well-organized, presentations carefully chosen, and overall it was a superb event and I hope to go every time they hold it. So make no mistake, it wasn't the Retreat itself.

But I came home feeling totally defeated. I didn't meet many who would traditionally be called craftspersons or artisans; there were potters, a fashion designer, and I believe, more than one furniture makers, but most textile people I met were textile artists, many using multi-media, some putting their 3-dimensional work into picture frames. Museum and gallery representatives were overwhelmingly interested in paintings and installations. Almost all the works on display were not utilitarian. In-vogue "craft" magazine are filled with unusable artistic crap. So many galleries declared: "we don't do textiles." And most devastating of all, the message I got from those who buy and curate was: "Don't call us; we'll call you."

So, what happened to craft? What happened to making beautiful things that work; that never-ending appreciation of holding something you use and having a good look once in a while to have your breath taken by its beauty, and the blending of aesthetics and utility? Is there no room for such "tools" in this mass-producing, mass-consuming, over-advertised world except for industrial, stretchable, one-size-fits-all polar fleece junk with the same logo?

I'm really at a loss as to where I am, and I feel the loss for the world. For now.

While working on the previous post, I got used to thinking of myself as an artists whose discipline is textiles; handweaving to be precise. In spite of the superbly organized Retreat, and making new friends, I came home feeling defeated because I felt a chasm between pure art (the kind you can't use) and applied art/craft (things with utility and beauty). I was not sure where I was heading, and I wasn't sure where my textiles fitted in the scheme of things.

The title comes from a chart I made in 2000 which shows pure artist (who may use fiber) at one end, and cottage-industry-production-weaver at the other, and pin-pointing where I wanted to be; it is my visual mission statement.

ARTIST/CRAFTSPERSON CONTINUUM

Drafted June 2006

I was very happy being an artist last week; I want to weave artistic, unique pieces of shawls, scarves and yardage that are wonderful to the touch, beautiful to look at, but are hard wearing serious textiles. But of course the story didn't end there.

For the first forty years of my life, I believed, "of course the glass is half full, and look, if you bend your knees this way, it looks more like 3/4 full!" But of late, I not only see that it's half-empty, but in certain lights, I looks completely empty. This week, it's not just empty, the glass is dirty!

I attended an Artists Retreat at St Arnaud this past weekend; it was well-organized, presentations carefully chosen, and overall it was a superb event and I hope to go every time they hold it. So make no mistake, it wasn't the Retreat itself.

But I came home feeling totally defeated. I didn't meet many who would traditionally be called craftspersons or artisans; there were potters, a fashion designer, and I believe, more than one furniture makers, but most textile people I met were textile artists, many using multi-media, some putting their 3-dimensional work into picture frames. Museum and gallery representatives were overwhelmingly interested in paintings and installations. Almost all the works on display were not utilitarian. In-vogue "craft" magazine are filled with unusable artistic crap. So many galleries declared: "we don't do textiles." And most devastating of all, the message I got from those who buy and curate was: "Don't call us; we'll call you."

So, what happened to craft? What happened to making beautiful things that work; that never-ending appreciation of holding something you use and having a good look once in a while to have your breath taken by its beauty, and the blending of aesthetics and utility? Is there no room for such "tools" in this mass-producing, mass-consuming, over-advertised world except for industrial, stretchable, one-size-fits-all polar fleece junk with the same logo?

I'm really at a loss as to where I am, and I feel the loss for the world. For now.

Who Do You Think You Are, Calling Yourself a Weaver?!

I started this post in May while thinking about what kind of a weaver I want to be and not being able to actually weave because of tendonitis. I have not reached a conclusion, but I now have a direction, so it's a good time to post while I'm looking at the end of an eventful weaving year.

This and the next two posts are dedicated to my oldest (in the length of time I've known her; she is younger than me, to be sure) friend Liz Backlund.

Liz, I used to think once we grew up, we knew where we were and who we were and parts of life would become automatic. Well, some parts may have, but not in the ones I anticipated. The search for our places seem to be on still, so we might as well enjoy the ride. I'm thinking Valley Fair.

WHO DO YOU THINK YOU ARE, CALLING YOURSELF A WEAVER?!

Drafted May 2006

I came to weaving late in my life. As a child I thought I would become an academic; that was the family business and I grew up on a college campus. I had very clear visions of me sitting in an office with wall-sized bookshelves on at least two sides and a twin-bed-sized dark wooden desk.

But now I live in a town without a university. And a strange place this is. What you need to understand is New Zealand is an extremely forgiving country to someone coming from an "old" country like myself; anyone can have a go at just about anything regardless of training, family background or other inherited baggage, and in Nelson, arts and crafts are all around, constantly seducing me to the colorful side.

Having enjoyed a few warps as a hobby weaver, I had hoped to sell my work eventually, but life interfered and I took this step earlier than I had planned. I attended small business seminars, I did market research, I made short-, mid-, and long-term plans, color-coordinated checklists and Gantt charts. And made To Do lists; notebooks of To Do lists.

And I wove. Weaving itself was fun, and considering where I started, I improved with every warp. But becoming a weaver was a different game. I was basing my new life on the familiar system of Gantt charts and To Do lists: weave an average of x pieces in y weeks; make $z sale every quarter, or roughly $z*3 by Year End. Slow was not good, and experimenting to improve designs could interfere with the plans. I had faith my improvements would come in direct proportion to the number of pieces I wove. Well, almost.

That I wove was itself a secret for a long time and I didn't show anyone my work. On 5 February 2001, 10 minutes before attending my first ever weaving workshop, I was left standing in a Blenheim church car park, watching Ben's Pajero heading back west, feeling worse than a kid on his first day of school. This was my day of reckoning, my coming out.

For a few years, when I ran into former work colleagues, I cautiously said I was "trying to be a weaver." I was trying to learn what kind of a life a weaver lives, not just weaving, studying colors, studying design, or learning to draw, but the other stuff. I even lived the tree months of Julia Cameron's The Artist's Way. Then I stopped going to marketing classes.

After six years, I haven't yet found out what a weaver's life is, but I know weaving is slow, and I can't live by the plans, at least not the ones I created back then. I need time to observe, to see, and be inspired. I need to allow myself to be reactive as well as proactive. I need to play more with colors and textures, and not put on a warp knowing exactly what is coming off it. And weave more.

And I need to allow myself to call me a weaver, because in this journey, there is no Commencement, there is no Diploma, I won't have letters at the end of my name to say I have arrived. I am a weaver because I weave.

This and the next two posts are dedicated to my oldest (in the length of time I've known her; she is younger than me, to be sure) friend Liz Backlund.

Liz, I used to think once we grew up, we knew where we were and who we were and parts of life would become automatic. Well, some parts may have, but not in the ones I anticipated. The search for our places seem to be on still, so we might as well enjoy the ride. I'm thinking Valley Fair.

WHO DO YOU THINK YOU ARE, CALLING YOURSELF A WEAVER?!

Drafted May 2006

I came to weaving late in my life. As a child I thought I would become an academic; that was the family business and I grew up on a college campus. I had very clear visions of me sitting in an office with wall-sized bookshelves on at least two sides and a twin-bed-sized dark wooden desk.

But now I live in a town without a university. And a strange place this is. What you need to understand is New Zealand is an extremely forgiving country to someone coming from an "old" country like myself; anyone can have a go at just about anything regardless of training, family background or other inherited baggage, and in Nelson, arts and crafts are all around, constantly seducing me to the colorful side.

Having enjoyed a few warps as a hobby weaver, I had hoped to sell my work eventually, but life interfered and I took this step earlier than I had planned. I attended small business seminars, I did market research, I made short-, mid-, and long-term plans, color-coordinated checklists and Gantt charts. And made To Do lists; notebooks of To Do lists.

And I wove. Weaving itself was fun, and considering where I started, I improved with every warp. But becoming a weaver was a different game. I was basing my new life on the familiar system of Gantt charts and To Do lists: weave an average of x pieces in y weeks; make $z sale every quarter, or roughly $z*3 by Year End. Slow was not good, and experimenting to improve designs could interfere with the plans. I had faith my improvements would come in direct proportion to the number of pieces I wove. Well, almost.

That I wove was itself a secret for a long time and I didn't show anyone my work. On 5 February 2001, 10 minutes before attending my first ever weaving workshop, I was left standing in a Blenheim church car park, watching Ben's Pajero heading back west, feeling worse than a kid on his first day of school. This was my day of reckoning, my coming out.

For a few years, when I ran into former work colleagues, I cautiously said I was "trying to be a weaver." I was trying to learn what kind of a life a weaver lives, not just weaving, studying colors, studying design, or learning to draw, but the other stuff. I even lived the tree months of Julia Cameron's The Artist's Way. Then I stopped going to marketing classes.

After six years, I haven't yet found out what a weaver's life is, but I know weaving is slow, and I can't live by the plans, at least not the ones I created back then. I need time to observe, to see, and be inspired. I need to allow myself to be reactive as well as proactive. I need to play more with colors and textures, and not put on a warp knowing exactly what is coming off it. And weave more.

And I need to allow myself to call me a weaver, because in this journey, there is no Commencement, there is no Diploma, I won't have letters at the end of my name to say I have arrived. I am a weaver because I weave.

2006/12/25

Randy Revisited on Christmas Day

I was threading my navy/teal silk/cashmere warp on my 4-shaft jack in 8-end Dornick, (that's a twill that changes direction every eight warp yarns) while thinking of Randy this evening.

I like regular, square-looking, or symmetrical weaves. I like stripes. I like single-colored plain weave with plenty of tracking. But there is a part of me which started to believe that in order to progress, I needed to include more and more Randy elements in my textiles, and this made me a little sad about having to depart from static (as opposed to his dynamic) textiles.

But I think progress in weaving is not linear. So while I intend to continue investigating the Art of Randying, I am allowed to delve deeper into symmetrical and regularly repeating patterns as well.

I think this is what he meant by my doing my apprenticeship.

I like regular, square-looking, or symmetrical weaves. I like stripes. I like single-colored plain weave with plenty of tracking. But there is a part of me which started to believe that in order to progress, I needed to include more and more Randy elements in my textiles, and this made me a little sad about having to depart from static (as opposed to his dynamic) textiles.

But I think progress in weaving is not linear. So while I intend to continue investigating the Art of Randying, I am allowed to delve deeper into symmetrical and regularly repeating patterns as well.

I think this is what he meant by my doing my apprenticeship.

2006/12/14

How I Make a Shawl: The Two Candidates

I believe good shawls age like good wine. I was unhappy with both of these last week, and refused to photograph them, but today, they didn't look.... so bad.

The yarns I used in this first warp were in three blues and one undyed 100% merino wool, 110/2. The sett was 18 DPI.

For this first piece, I used a variegated-dyed merino boucle in the weft. The weave is #40229 from Kris Bruland's Handweaing.net. The weft shrunk far more than I had anticipated, so the shawl has a squishy, stretchy texture, but is surprisingly light-weight.

For this first piece, I used a variegated-dyed merino boucle in the weft. The weave is #40229 from Kris Bruland's Handweaing.net. The weft shrunk far more than I had anticipated, so the shawl has a squishy, stretchy texture, but is surprisingly light-weight.

I had anticipated the loops on the boucle to pop up all over, making it a piece showing off the beautiful oranges and greens of the weft yarn, but the result is more warp-dominant. I don't like that the construction is not exactly stable, (i.e. the long warp floats might catch buttons and long earrings, but pulling it warp-wise and weft-wise, the thread will go right back into the textile); on the other hand, I think it looks like water over sea weeds and shells.

In the second piece, possum/mohair/merino wefts in four colors were placed in Fibonacci sequence, the colors representing grass, sand, shallow and deeper water. The weave is #12833 from the same, turned.

In the second piece, possum/mohair/merino wefts in four colors were placed in Fibonacci sequence, the colors representing grass, sand, shallow and deeper water. The weave is #12833 from the same, turned.

I didn't like the teal yarn being much more vivid than the other three, and even though all four colors were used in the same proportion, the shawl appear predominantly teal. As well, in spite of sampling, the finished textile is much stiffer owing to the weave structure; this is totally different from the shawls I usually weave with the exact same combination of warp and weft yarns and the sett, but woven in looser twills. The appearance and the hand of this piece ended up being masculine/rustic/tough, which is not the kind of textile I normally weave, like, or had planned, but the appearance matches the hand, and this is a sturdy, long-lasting piece of cloth.

I am not sure if these pieces will make it into the final selection. I tried to challenge my self-imposed boundaries and preconceptions, and I created two pieces that I would not have woven had I not tried new things. Yes, I am ambivalent about these at this point, but I also feel both of these suit "Sea, Sand and Sky".

The yarns I used in this first warp were in three blues and one undyed 100% merino wool, 110/2. The sett was 18 DPI.

For this first piece, I used a variegated-dyed merino boucle in the weft. The weave is #40229 from Kris Bruland's Handweaing.net. The weft shrunk far more than I had anticipated, so the shawl has a squishy, stretchy texture, but is surprisingly light-weight.

For this first piece, I used a variegated-dyed merino boucle in the weft. The weave is #40229 from Kris Bruland's Handweaing.net. The weft shrunk far more than I had anticipated, so the shawl has a squishy, stretchy texture, but is surprisingly light-weight.I had anticipated the loops on the boucle to pop up all over, making it a piece showing off the beautiful oranges and greens of the weft yarn, but the result is more warp-dominant. I don't like that the construction is not exactly stable, (i.e. the long warp floats might catch buttons and long earrings, but pulling it warp-wise and weft-wise, the thread will go right back into the textile); on the other hand, I think it looks like water over sea weeds and shells.

In the second piece, possum/mohair/merino wefts in four colors were placed in Fibonacci sequence, the colors representing grass, sand, shallow and deeper water. The weave is #12833 from the same, turned.

In the second piece, possum/mohair/merino wefts in four colors were placed in Fibonacci sequence, the colors representing grass, sand, shallow and deeper water. The weave is #12833 from the same, turned.I didn't like the teal yarn being much more vivid than the other three, and even though all four colors were used in the same proportion, the shawl appear predominantly teal. As well, in spite of sampling, the finished textile is much stiffer owing to the weave structure; this is totally different from the shawls I usually weave with the exact same combination of warp and weft yarns and the sett, but woven in looser twills. The appearance and the hand of this piece ended up being masculine/rustic/tough, which is not the kind of textile I normally weave, like, or had planned, but the appearance matches the hand, and this is a sturdy, long-lasting piece of cloth.

I am not sure if these pieces will make it into the final selection. I tried to challenge my self-imposed boundaries and preconceptions, and I created two pieces that I would not have woven had I not tried new things. Yes, I am ambivalent about these at this point, but I also feel both of these suit "Sea, Sand and Sky".

How I Make a Shawl - Part 7: Fringing, Embellishing, Wet Finishing, Pressing and Drying

.JPG) After the shawl rested overnight (or longer), I needed to fringe. This can be an art in itself, twisting, braiding, and weaving the fringes like lattice work, but there were enough interest in the colors and textures in these two, so I made straight forward fringes. The fringes took about 2 hours per shawl, with frequent rests and counting/recounting.

After the shawl rested overnight (or longer), I needed to fringe. This can be an art in itself, twisting, braiding, and weaving the fringes like lattice work, but there were enough interest in the colors and textures in these two, so I made straight forward fringes. The fringes took about 2 hours per shawl, with frequent rests and counting/recounting.Sometimes I like to embellish the selvedge/s or the fringes with tiny glass beads, which makes parts of the shawls sparkle in the night, but again, I didn't want to make these two pieces too busy, so I didn't embellish them.

.JPG) Then came the last but very exciting part of "weaving": wet finishing is mostly washing, but in case of wool, it also involves controlled felting, so here I did to wool what your mother probably told you never to do to your brand new sweater.

Then came the last but very exciting part of "weaving": wet finishing is mostly washing, but in case of wool, it also involves controlled felting, so here I did to wool what your mother probably told you never to do to your brand new sweater.This is our old bathtub which we had fitted into a cradle. I have the hot water tap in the middle of the garage, just next to the lawn mower, and the cold water and drain at the end.

.JPG)

.JPG) The very first time a shawl is placed in hot soapy water, it is left alone for about 15 minutes so it can absorb the water at its own speed, and the fiber can open up.

The very first time a shawl is placed in hot soapy water, it is left alone for about 15 minutes so it can absorb the water at its own speed, and the fiber can open up..JPG) I washed them in hot soapy water roughly, then plunged them into cold water, and repeated the process. I must watch the transformation of the cloth carefully while I wet finish, but normally, with the combination of the yarns I use, the transformation takes place in the second hot wash, and I rinse the cloth carefully in the last cold wash. The first piece on this warp needed another extra hot wash, but the second was, as predicted, a two-cycle finish. I wash every single piece individually for this reason.

I washed them in hot soapy water roughly, then plunged them into cold water, and repeated the process. I must watch the transformation of the cloth carefully while I wet finish, but normally, with the combination of the yarns I use, the transformation takes place in the second hot wash, and I rinse the cloth carefully in the last cold wash. The first piece on this warp needed another extra hot wash, but the second was, as predicted, a two-cycle finish. I wash every single piece individually for this reason.The photo above is during the most exciting second hot wash, and if you click to enlarge, you can see how the wiry/netty warp and weft yarns have integrated to become a piece of cloth.

After I squeezed as much water as I could, I spun the shawls in medium speed in my washing machine for a while, repositioned them, and then spun in high speed.

.JPG) Finally the pieces were steam-pressed over and over while still damp, and laid flat on the living room floor to dry overnight. Wet finishing and pressing took about an hour for each piece.

Finally the pieces were steam-pressed over and over while still damp, and laid flat on the living room floor to dry overnight. Wet finishing and pressing took about an hour for each piece.After the pieces were completely dry, I cut off the frizzy ends below the knot of each fringe, and that is the very last job, which took about 15 minutes for each shawl.

I Used the Wrong Weft!!

I thought I was weaving with a yellow-green 100% cashmere yarn, and though the cloth took on a blueish color on the loom, I thought it was because of the two grays in the warp. I thought nothing of it while fringing, washing or pressing, though the texture did feel slightly stiffer, and the green weft shone more than expected.

I thought I was weaving with a yellow-green 100% cashmere yarn, and though the cloth took on a blueish color on the loom, I thought it was because of the two grays in the warp. I thought nothing of it while fringing, washing or pressing, though the texture did feel slightly stiffer, and the green weft shone more than expected.It wasn't until I was fishing through my cashmere box that I noticed this cone was labeled incorrectly, and then realized I used the melon-glacé-colored cashmere-silk mix instead. I like the contrast in the sheen, and the way the silk-mix sits slightly above the cashmere warp to show off the weave structure.

For once, Ben was given a piece not because I had made too many mistakes, but because the overall color is one of his favorites.

Men's Cashmere Scarves

Men's mean they are just a little more densely woven, and are wider. Warp in two grays; one scarf is with weft in clear yellow, another in dirty yellow. 100% cashmere.

Men's mean they are just a little more densely woven, and are wider. Warp in two grays; one scarf is with weft in clear yellow, another in dirty yellow. 100% cashmere.The clear yellow is a Christmas present from my friend Joan to her friend; the dirty yellow is a present for my baby brother for taking a giant step in his career earlier in the year.

2006/12/07

How I Make a Shawl - Part 6: Finally the Weaving

The act of weaving is simple and quick: I stepped on the pedal;

The act of weaving is simple and quick: I stepped on the pedal; waited for the shafts to lift, (this photo is crocked, but the shafts lifted evenly, or else I needed to tweak the height of the shafts);

waited for the shafts to lift, (this photo is crocked, but the shafts lifted evenly, or else I needed to tweak the height of the shafts); threw the shuttle between the lifted and the not-lifted threads, (this space is called the "shed");

threw the shuttle between the lifted and the not-lifted threads, (this space is called the "shed"); and brought the reed forward to position the weft, (this action is called "beating"). Every few inches, I advanced the warp threads and continued weaving.

and brought the reed forward to position the weft, (this action is called "beating"). Every few inches, I advanced the warp threads and continued weaving.I wove two pieces of samples, fringed, washed, pressed and dried them to test six weft candidates and five weave structures. I decided on the weft and the weave structure for the first shawl, and wove it, which took a little less than three hours. I decided on the weft yarns, color schemes and the weave structure of the second shawl while I was weaving the first; the weft color distribution took about half an hour to calculate, and the weaving time was a little over three hours on the second shawl.

After I wove the length of the shawl, I advanced the warp enough to get fringes, and cut off the woven shawl. I checked for mistakes or bits of yarn sticking out of the cloth, cut then off, and hung the shawl overnight to rest.

How I Make a Shawl - Part 5: Switching on the Loom

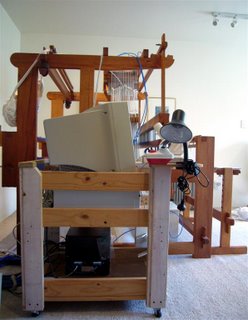

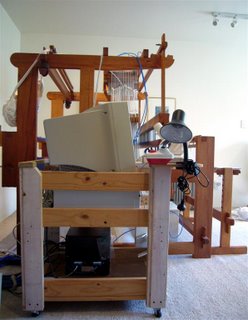

With some looms, non-dobby foot looms, there is another process called tie-up, but because I am weaving this series on a computer-controlled loom, I don't have to crawl under the loom to connect the treadles (foot pedals) to the shafts according to the weave structure; this is a relatively short and straight-forward process, unless you have not enough room under the loom and need to test your contortionist skills. (I do this when weaving on my Jack loom.)

A computer-controlled loom (which is not a special loom as much as it has lots of extra parts) can read a weave structure designed (or downloaded) on the computer, in a graph-like format called a draft, and decide which shaft/s is/are lifted in what order.

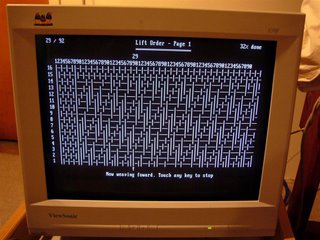

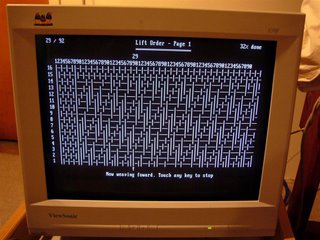

In my case, I needed to switch on the computer, open the program that translates the draft into the lifting order, and select the weave structure I want to sample;

In my case, I needed to switch on the computer, open the program that translates the draft into the lifting order, and select the weave structure I want to sample;

then I switched on the air compressor in the garage to power the physical lifting, (the car is not attached to the compressor; Ben needs to park this close so the garage door can be closed);

then I switched on the air compressor in the garage to power the physical lifting, (the car is not attached to the compressor; Ben needs to park this close so the garage door can be closed);

and I switched on the black box which conveys the lifting order to the solenoids.

and I switched on the black box which conveys the lifting order to the solenoids.

Oh, and I prepared the weft samples by winding them onto pirns that goes into the shuttle.

Oh, and I prepared the weft samples by winding them onto pirns that goes into the shuttle.

My workstation is all ready to roar in less than 60 seconds. (The air compressor in the garage is behind the wall to the left.)

My workstation is all ready to roar in less than 60 seconds. (The air compressor in the garage is behind the wall to the left.)

A computer-controlled loom (which is not a special loom as much as it has lots of extra parts) can read a weave structure designed (or downloaded) on the computer, in a graph-like format called a draft, and decide which shaft/s is/are lifted in what order.

In my case, I needed to switch on the computer, open the program that translates the draft into the lifting order, and select the weave structure I want to sample;

In my case, I needed to switch on the computer, open the program that translates the draft into the lifting order, and select the weave structure I want to sample; then I switched on the air compressor in the garage to power the physical lifting, (the car is not attached to the compressor; Ben needs to park this close so the garage door can be closed);

then I switched on the air compressor in the garage to power the physical lifting, (the car is not attached to the compressor; Ben needs to park this close so the garage door can be closed); and I switched on the black box which conveys the lifting order to the solenoids.

and I switched on the black box which conveys the lifting order to the solenoids. Oh, and I prepared the weft samples by winding them onto pirns that goes into the shuttle.

Oh, and I prepared the weft samples by winding them onto pirns that goes into the shuttle. My workstation is all ready to roar in less than 60 seconds. (The air compressor in the garage is behind the wall to the left.)

My workstation is all ready to roar in less than 60 seconds. (The air compressor in the garage is behind the wall to the left.)

How I Make a Shawl - Part 4: Dressing the Loom - Winding and Through the Reed

Next was the most dreaded, unnerving (for me) part of the entire weaving experience, the winding, the only step where I need Ben's help.

Theoretically, all I need to do is to wind handles attached to the back beam so the warp threads in the warp chain is straightened and wound on to the back beam, which can later be wound forward under tension to be woven. The reality is, warp yarns can get tangled with each other, the threads may be unevenly tensioned, or depending on the type of threads, it can get tangled up with the heddle, and even break, so the winding needs to be done under vary careful and as many watchful eyes as possible. This is the only part of weaving that I really dislike.

Theoretically, all I need to do is to wind handles attached to the back beam so the warp threads in the warp chain is straightened and wound on to the back beam, which can later be wound forward under tension to be woven. The reality is, warp yarns can get tangled with each other, the threads may be unevenly tensioned, or depending on the type of threads, it can get tangled up with the heddle, and even break, so the winding needs to be done under vary careful and as many watchful eyes as possible. This is the only part of weaving that I really dislike.

But I must wind to weave, so I attached a raddle on the front beam which allowed me to spread the warp relatively evenly to the width of the shawl; Ben held the warp chain, which was gradually undone by him and the threads held under even tension, at the other side of the room, as I slowly wound the warp.

But I must wind to weave, so I attached a raddle on the front beam which allowed me to spread the warp relatively evenly to the width of the shawl; Ben held the warp chain, which was gradually undone by him and the threads held under even tension, at the other side of the room, as I slowly wound the warp.

I must have taken this from where I was kneeling while Ben was resting his arms because the warp threads are slack; we watched the back beam, above and below the threads, the front and the back of the heddles and the front and back of the raddle for loose or tangled warp threads. The slats of wood and old plastic Venetian blinds help separate the different layers of warp threads.

I must have taken this from where I was kneeling while Ben was resting his arms because the warp threads are slack; we watched the back beam, above and below the threads, the front and the back of the heddles and the front and back of the raddle for loose or tangled warp threads. The slats of wood and old plastic Venetian blinds help separate the different layers of warp threads.

We stopped winding when I had about 40cm left in front of the raddle; Ben left the rest of the warp threads hanging and I came to the front of the loom. I removed the raddle, and inserted a 6-dent reed. The reed spreads the warp threads evenly in the exact weaving width; I am using a 6-dent reed, which has six slots for every inch.

I wanted to weave this shawl at 18 ends (warp threads) per inch, so threaded three threads in every slot. When I weave, the bars in the reed helps me push the weft threads forward and into position.

I wanted to weave this shawl at 18 ends (warp threads) per inch, so threaded three threads in every slot. When I weave, the bars in the reed helps me push the weft threads forward and into position.

The winding took about an hour; the threading through the reed about another hour. Now I can tie the warp threads on to the front beam, and start weaving. Because I was not happy with the unevenness of the tension, I tied the warp threads directly, tugging at some sections more than the other, fine-tuning the tension.

The winding took about an hour; the threading through the reed about another hour. Now I can tie the warp threads on to the front beam, and start weaving. Because I was not happy with the unevenness of the tension, I tied the warp threads directly, tugging at some sections more than the other, fine-tuning the tension.

PS. A week later, I tied each new warp thread of the second warp onto the ends of the first warp, thus eliminating the need for threading through the heddles or the reed; the tying took me almost half a day, but this was still a great time-saver. I increased the number of warp threads slightly, so you can see the very long pink leaders, reaching all the way to the back beam, to make up the difference. The second warp is the more intense mid-blue only.

PS. A week later, I tied each new warp thread of the second warp onto the ends of the first warp, thus eliminating the need for threading through the heddles or the reed; the tying took me almost half a day, but this was still a great time-saver. I increased the number of warp threads slightly, so you can see the very long pink leaders, reaching all the way to the back beam, to make up the difference. The second warp is the more intense mid-blue only.

Theoretically, all I need to do is to wind handles attached to the back beam so the warp threads in the warp chain is straightened and wound on to the back beam, which can later be wound forward under tension to be woven. The reality is, warp yarns can get tangled with each other, the threads may be unevenly tensioned, or depending on the type of threads, it can get tangled up with the heddle, and even break, so the winding needs to be done under vary careful and as many watchful eyes as possible. This is the only part of weaving that I really dislike.

Theoretically, all I need to do is to wind handles attached to the back beam so the warp threads in the warp chain is straightened and wound on to the back beam, which can later be wound forward under tension to be woven. The reality is, warp yarns can get tangled with each other, the threads may be unevenly tensioned, or depending on the type of threads, it can get tangled up with the heddle, and even break, so the winding needs to be done under vary careful and as many watchful eyes as possible. This is the only part of weaving that I really dislike. But I must wind to weave, so I attached a raddle on the front beam which allowed me to spread the warp relatively evenly to the width of the shawl; Ben held the warp chain, which was gradually undone by him and the threads held under even tension, at the other side of the room, as I slowly wound the warp.

But I must wind to weave, so I attached a raddle on the front beam which allowed me to spread the warp relatively evenly to the width of the shawl; Ben held the warp chain, which was gradually undone by him and the threads held under even tension, at the other side of the room, as I slowly wound the warp. I must have taken this from where I was kneeling while Ben was resting his arms because the warp threads are slack; we watched the back beam, above and below the threads, the front and the back of the heddles and the front and back of the raddle for loose or tangled warp threads. The slats of wood and old plastic Venetian blinds help separate the different layers of warp threads.

I must have taken this from where I was kneeling while Ben was resting his arms because the warp threads are slack; we watched the back beam, above and below the threads, the front and the back of the heddles and the front and back of the raddle for loose or tangled warp threads. The slats of wood and old plastic Venetian blinds help separate the different layers of warp threads.We stopped winding when I had about 40cm left in front of the raddle; Ben left the rest of the warp threads hanging and I came to the front of the loom. I removed the raddle, and inserted a 6-dent reed. The reed spreads the warp threads evenly in the exact weaving width; I am using a 6-dent reed, which has six slots for every inch.

I wanted to weave this shawl at 18 ends (warp threads) per inch, so threaded three threads in every slot. When I weave, the bars in the reed helps me push the weft threads forward and into position.

I wanted to weave this shawl at 18 ends (warp threads) per inch, so threaded three threads in every slot. When I weave, the bars in the reed helps me push the weft threads forward and into position. The winding took about an hour; the threading through the reed about another hour. Now I can tie the warp threads on to the front beam, and start weaving. Because I was not happy with the unevenness of the tension, I tied the warp threads directly, tugging at some sections more than the other, fine-tuning the tension.

The winding took about an hour; the threading through the reed about another hour. Now I can tie the warp threads on to the front beam, and start weaving. Because I was not happy with the unevenness of the tension, I tied the warp threads directly, tugging at some sections more than the other, fine-tuning the tension. PS. A week later, I tied each new warp thread of the second warp onto the ends of the first warp, thus eliminating the need for threading through the heddles or the reed; the tying took me almost half a day, but this was still a great time-saver. I increased the number of warp threads slightly, so you can see the very long pink leaders, reaching all the way to the back beam, to make up the difference. The second warp is the more intense mid-blue only.

PS. A week later, I tied each new warp thread of the second warp onto the ends of the first warp, thus eliminating the need for threading through the heddles or the reed; the tying took me almost half a day, but this was still a great time-saver. I increased the number of warp threads slightly, so you can see the very long pink leaders, reaching all the way to the back beam, to make up the difference. The second warp is the more intense mid-blue only.

How I Make a Shawl - Part 3: Dressing the Loom - Though the Heddles

Now come three tedious but important steps, which, collectively are called "dressing" the loom.

After making a long warp chain and transporting it downstairs, I secured most of the chain to the front of the loom, and stood in the space behind the heddles and shafts, in front of the back beam, and one by one, threaded the warp threads in to the eye of the heddle on the appropriate shaft and in the planned order.

After making a long warp chain and transporting it downstairs, I secured most of the chain to the front of the loom, and stood in the space behind the heddles and shafts, in front of the back beam, and one by one, threaded the warp threads in to the eye of the heddle on the appropriate shaft and in the planned order.

Heddles are the white string-like things with an "eye" though which normally one warp thread is threaded; every heddle is held by a shaft or a harness, (the pieces of wood at the top and the bottom on this loom); each set of heddles on the same shaft behave in unison.

Heddles are the white string-like things with an "eye" though which normally one warp thread is threaded; every heddle is held by a shaft or a harness, (the pieces of wood at the top and the bottom on this loom); each set of heddles on the same shaft behave in unison.

Now, weave structures (or patterns) are created by selectively lifting (and on some looms also lowering) shaft/s so the shuttle and the weft threads can pass through some lifted and some not-lifted (or lowered) threads. You could say that the threading (first thread on the left is threaded on Shaft A, the next on Shaft B...), and the lifting of the shafts create the structure. I know it's getting a little technical, but if you see them in action, it's rather very simple.

Now, weave structures (or patterns) are created by selectively lifting (and on some looms also lowering) shaft/s so the shuttle and the weft threads can pass through some lifted and some not-lifted (or lowered) threads. You could say that the threading (first thread on the left is threaded on Shaft A, the next on Shaft B...), and the lifting of the shafts create the structure. I know it's getting a little technical, but if you see them in action, it's rather very simple.

I have 16 shafts on this loom, but usually I save Shafts 15 and 16 to weave plain weave on the two edges so I don't have to worry about the weft slipping at the edges, leaving me 14 shafts to play with the weave structure. Because I want to test several structures and weave at least two shawls, I threaded this warp in the simplest and most flexible threading, the straight draw. So, working from behind the shafts, the first warp thread (which will be on the far left when I sit in front of the loom to weave) was threaded through the eye of the heddle on Shaft 16, the one closest to me; the next, on Shaft 15; then the next 494 threads were threaded in shafts 14, 13, 12, 11, and so on to 1, and resuming at 14. The last two, 497 and 498, were on Shafts 16 and 15 again.

Threading the warp threads through the heddles is a simple task, but if mistakes are made, correcting the threading can be annoying, so I prefer to work on only 200-300 warp threads at a time. For this I warp, I worked two afternoons (when the light was better) to thread and check.

When all seemed good, I secured the warp ends to the back beam; because this is a large loom and the loom waste (the portion of the warp that cannot be brought forward to weave) is great, so I added a little bit of what I call the leaders in the end.

When all seemed good, I secured the warp ends to the back beam; because this is a large loom and the loom waste (the portion of the warp that cannot be brought forward to weave) is great, so I added a little bit of what I call the leaders in the end.

The two white threads appearing above the rest were threaded not in the eye, but the space above by mistake. This needed correcting before I could wind the warp onto the back beam.

After making a long warp chain and transporting it downstairs, I secured most of the chain to the front of the loom, and stood in the space behind the heddles and shafts, in front of the back beam, and one by one, threaded the warp threads in to the eye of the heddle on the appropriate shaft and in the planned order.

After making a long warp chain and transporting it downstairs, I secured most of the chain to the front of the loom, and stood in the space behind the heddles and shafts, in front of the back beam, and one by one, threaded the warp threads in to the eye of the heddle on the appropriate shaft and in the planned order. Heddles are the white string-like things with an "eye" though which normally one warp thread is threaded; every heddle is held by a shaft or a harness, (the pieces of wood at the top and the bottom on this loom); each set of heddles on the same shaft behave in unison.

Heddles are the white string-like things with an "eye" though which normally one warp thread is threaded; every heddle is held by a shaft or a harness, (the pieces of wood at the top and the bottom on this loom); each set of heddles on the same shaft behave in unison. Now, weave structures (or patterns) are created by selectively lifting (and on some looms also lowering) shaft/s so the shuttle and the weft threads can pass through some lifted and some not-lifted (or lowered) threads. You could say that the threading (first thread on the left is threaded on Shaft A, the next on Shaft B...), and the lifting of the shafts create the structure. I know it's getting a little technical, but if you see them in action, it's rather very simple.

Now, weave structures (or patterns) are created by selectively lifting (and on some looms also lowering) shaft/s so the shuttle and the weft threads can pass through some lifted and some not-lifted (or lowered) threads. You could say that the threading (first thread on the left is threaded on Shaft A, the next on Shaft B...), and the lifting of the shafts create the structure. I know it's getting a little technical, but if you see them in action, it's rather very simple.I have 16 shafts on this loom, but usually I save Shafts 15 and 16 to weave plain weave on the two edges so I don't have to worry about the weft slipping at the edges, leaving me 14 shafts to play with the weave structure. Because I want to test several structures and weave at least two shawls, I threaded this warp in the simplest and most flexible threading, the straight draw. So, working from behind the shafts, the first warp thread (which will be on the far left when I sit in front of the loom to weave) was threaded through the eye of the heddle on Shaft 16, the one closest to me; the next, on Shaft 15; then the next 494 threads were threaded in shafts 14, 13, 12, 11, and so on to 1, and resuming at 14. The last two, 497 and 498, were on Shafts 16 and 15 again.

Threading the warp threads through the heddles is a simple task, but if mistakes are made, correcting the threading can be annoying, so I prefer to work on only 200-300 warp threads at a time. For this I warp, I worked two afternoons (when the light was better) to thread and check.

When all seemed good, I secured the warp ends to the back beam; because this is a large loom and the loom waste (the portion of the warp that cannot be brought forward to weave) is great, so I added a little bit of what I call the leaders in the end.

When all seemed good, I secured the warp ends to the back beam; because this is a large loom and the loom waste (the portion of the warp that cannot be brought forward to weave) is great, so I added a little bit of what I call the leaders in the end.The two white threads appearing above the rest were threaded not in the eye, but the space above by mistake. This needed correcting before I could wind the warp onto the back beam.

2006/12/06

How I Make a Shawl - Part 2: Measuring the Warp

The work of a weaver, the preparation, the actual weaving, and the finishing, is linear; that is, the work consists of a series of relatively simple tasks, but each step needs to be done in sequence.

After I decided to use three colors in the warp, I measured the 498 warp threads on the warping board, by wounding a single warp thread at a time around all the pegs on the board; this way I would get roughly eight meters of warp, which should give me plenty to sample and two or three shawls. In my house, I have a wall-mounted heater at just the right height in the hallway, so I propped the warping board on it. Behind me to the right is the stairway, and I placed the cones of yarn on different steps; this way, the yarn is pulled straight up off the cones, over the railing, and onto the board, so the cones didn't topple or dance around.

After I decided to use three colors in the warp, I measured the 498 warp threads on the warping board, by wounding a single warp thread at a time around all the pegs on the board; this way I would get roughly eight meters of warp, which should give me plenty to sample and two or three shawls. In my house, I have a wall-mounted heater at just the right height in the hallway, so I propped the warping board on it. Behind me to the right is the stairway, and I placed the cones of yarn on different steps; this way, the yarn is pulled straight up off the cones, over the railing, and onto the board, so the cones didn't topple or dance around.

As the warp threads accumulated, for the first time I saw the exact proportion of the yarns in the exact order they would be set up on the loom. Above is the busier half of the warp threads.

As the warp threads accumulated, for the first time I saw the exact proportion of the yarns in the exact order they would be set up on the loom. Above is the busier half of the warp threads.

This measuring process took me about 90 minutes, with long breaks and frequent checking and rechecking and lots of counting.

After I decided to use three colors in the warp, I measured the 498 warp threads on the warping board, by wounding a single warp thread at a time around all the pegs on the board; this way I would get roughly eight meters of warp, which should give me plenty to sample and two or three shawls. In my house, I have a wall-mounted heater at just the right height in the hallway, so I propped the warping board on it. Behind me to the right is the stairway, and I placed the cones of yarn on different steps; this way, the yarn is pulled straight up off the cones, over the railing, and onto the board, so the cones didn't topple or dance around.

After I decided to use three colors in the warp, I measured the 498 warp threads on the warping board, by wounding a single warp thread at a time around all the pegs on the board; this way I would get roughly eight meters of warp, which should give me plenty to sample and two or three shawls. In my house, I have a wall-mounted heater at just the right height in the hallway, so I propped the warping board on it. Behind me to the right is the stairway, and I placed the cones of yarn on different steps; this way, the yarn is pulled straight up off the cones, over the railing, and onto the board, so the cones didn't topple or dance around. As the warp threads accumulated, for the first time I saw the exact proportion of the yarns in the exact order they would be set up on the loom. Above is the busier half of the warp threads.

As the warp threads accumulated, for the first time I saw the exact proportion of the yarns in the exact order they would be set up on the loom. Above is the busier half of the warp threads.This measuring process took me about 90 minutes, with long breaks and frequent checking and rechecking and lots of counting.

How I Make a Shawl - Part 1: Planning/Designing

I'm often asked, "How long does it take to weave a shawl?"to which I have no quick answer. It depends on the purpose of the piece and/or the occasion of the gift, whether I know the person who will be wearing it and what I know about the person, the size of the piece and the yarn, the number of types and colors of yarns, weave structure (or pattern), and the loom, just to name a few. So, rather than giving you the days and hours I spent on a particular piece, I thought I'd take you on a short journey, of weaving two pieces from one warp in preparation of my Exhibit(ion).

Please note this is by no means a tutorial on how to weave. I am leaving out vital but boring technical information. And in weaving, there are always many different ways to accomplish the same thing; most weavers become comfortable over time with one method, which accommodates the body size, the loom type and size, the available equipment/assistance and space. (And this is also a disclaimer for my doing things other weavers and weaving teachers might cringe at if they only saw me.) I also lack confidence with proper weaving or design parlance, but with the help of a few photographs, I hope you get the feel of the work I do.

Unlike my usual work, (one-off pieces as special gifts or to be sent to juried exhibits), I need to weave a series of shawls which are interesting in their own right, but collectively not dissimilar, to give the Exhibit(ion) an visual cohesiveness. So I selected the sea as my theme. I placed cones of blue and white yarns all over the house so I was constantly looking at them and thinking about the theme.

Unlike my usual work, (one-off pieces as special gifts or to be sent to juried exhibits), I need to weave a series of shawls which are interesting in their own right, but collectively not dissimilar, to give the Exhibit(ion) an visual cohesiveness. So I selected the sea as my theme. I placed cones of blue and white yarns all over the house so I was constantly looking at them and thinking about the theme.

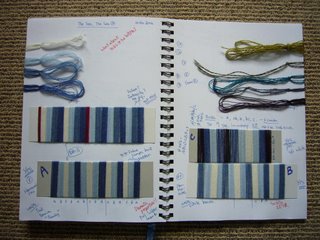

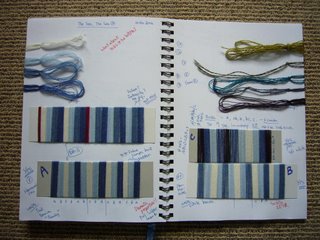

I narrowed down the yarns I can use as my warp (that is, the length-wise group of threads that will be 'attached' to the loom) and started playing with combinations. The small strips you see are called "wrapping", where warp candidates are wound around a small piece of cardboard. I don't usually do this, but because I needed to keep "the series" in mind and thought it best to keep good records, I made a few wrappings. The short time this took paid off as I did not like the look of my two mid-blues adjacent to each other (even though they look alright on cones sitting next to each other); the darker mid-blue was much more vivid/intense than the paler mid-blue. However the variegated powder blue looked good next to either mid-blue.

I narrowed down the yarns I can use as my warp (that is, the length-wise group of threads that will be 'attached' to the loom) and started playing with combinations. The small strips you see are called "wrapping", where warp candidates are wound around a small piece of cardboard. I don't usually do this, but because I needed to keep "the series" in mind and thought it best to keep good records, I made a few wrappings. The short time this took paid off as I did not like the look of my two mid-blues adjacent to each other (even though they look alright on cones sitting next to each other); the darker mid-blue was much more vivid/intense than the paler mid-blue. However the variegated powder blue looked good next to either mid-blue.

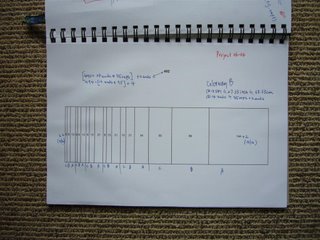

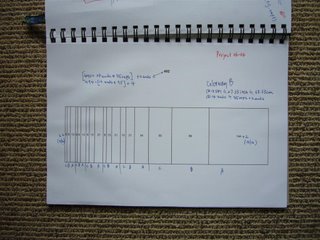

At the same time, I wanted to use my new knowledge of Fibonacci Sequence, so I had charts showing different proportions and arrangements, again, all over the house.

At the same time, I wanted to use my new knowledge of Fibonacci Sequence, so I had charts showing different proportions and arrangements, again, all over the house.

For the first warp, I decided to try the easiest option and place three colors, pale mid-blue, variegated powder blue, and undyed, to express waves on the beach. The order will be a simple repetition of mid-powder-undyed, and I need 494 warp threads for the design part, and two on each edges to secure, so a total of 498 warp threads. A more conscientious weaver might have colored in the chart or made a proportional wrapping, but I'm a waver, not a wrapper, so I moved on .

For the first warp, I decided to try the easiest option and place three colors, pale mid-blue, variegated powder blue, and undyed, to express waves on the beach. The order will be a simple repetition of mid-powder-undyed, and I need 494 warp threads for the design part, and two on each edges to secure, so a total of 498 warp threads. A more conscientious weaver might have colored in the chart or made a proportional wrapping, but I'm a waver, not a wrapper, so I moved on .

The design process is a long-drawn out one for me, because I see so many possibilities and I can't make up my mind. I started this about six months ago, and it will be on-going until I cut off the last piece from the last warp. From selecting the yarns for the first warp, deciding on the placement and proportion of the colors, and calculating the number of threads in each color took me approximately an half of an afternoon.

Please note this is by no means a tutorial on how to weave. I am leaving out vital but boring technical information. And in weaving, there are always many different ways to accomplish the same thing; most weavers become comfortable over time with one method, which accommodates the body size, the loom type and size, the available equipment/assistance and space. (And this is also a disclaimer for my doing things other weavers and weaving teachers might cringe at if they only saw me.) I also lack confidence with proper weaving or design parlance, but with the help of a few photographs, I hope you get the feel of the work I do.

Unlike my usual work, (one-off pieces as special gifts or to be sent to juried exhibits), I need to weave a series of shawls which are interesting in their own right, but collectively not dissimilar, to give the Exhibit(ion) an visual cohesiveness. So I selected the sea as my theme. I placed cones of blue and white yarns all over the house so I was constantly looking at them and thinking about the theme.

Unlike my usual work, (one-off pieces as special gifts or to be sent to juried exhibits), I need to weave a series of shawls which are interesting in their own right, but collectively not dissimilar, to give the Exhibit(ion) an visual cohesiveness. So I selected the sea as my theme. I placed cones of blue and white yarns all over the house so I was constantly looking at them and thinking about the theme. I narrowed down the yarns I can use as my warp (that is, the length-wise group of threads that will be 'attached' to the loom) and started playing with combinations. The small strips you see are called "wrapping", where warp candidates are wound around a small piece of cardboard. I don't usually do this, but because I needed to keep "the series" in mind and thought it best to keep good records, I made a few wrappings. The short time this took paid off as I did not like the look of my two mid-blues adjacent to each other (even though they look alright on cones sitting next to each other); the darker mid-blue was much more vivid/intense than the paler mid-blue. However the variegated powder blue looked good next to either mid-blue.

I narrowed down the yarns I can use as my warp (that is, the length-wise group of threads that will be 'attached' to the loom) and started playing with combinations. The small strips you see are called "wrapping", where warp candidates are wound around a small piece of cardboard. I don't usually do this, but because I needed to keep "the series" in mind and thought it best to keep good records, I made a few wrappings. The short time this took paid off as I did not like the look of my two mid-blues adjacent to each other (even though they look alright on cones sitting next to each other); the darker mid-blue was much more vivid/intense than the paler mid-blue. However the variegated powder blue looked good next to either mid-blue. At the same time, I wanted to use my new knowledge of Fibonacci Sequence, so I had charts showing different proportions and arrangements, again, all over the house.

At the same time, I wanted to use my new knowledge of Fibonacci Sequence, so I had charts showing different proportions and arrangements, again, all over the house. For the first warp, I decided to try the easiest option and place three colors, pale mid-blue, variegated powder blue, and undyed, to express waves on the beach. The order will be a simple repetition of mid-powder-undyed, and I need 494 warp threads for the design part, and two on each edges to secure, so a total of 498 warp threads. A more conscientious weaver might have colored in the chart or made a proportional wrapping, but I'm a waver, not a wrapper, so I moved on .

For the first warp, I decided to try the easiest option and place three colors, pale mid-blue, variegated powder blue, and undyed, to express waves on the beach. The order will be a simple repetition of mid-powder-undyed, and I need 494 warp threads for the design part, and two on each edges to secure, so a total of 498 warp threads. A more conscientious weaver might have colored in the chart or made a proportional wrapping, but I'm a waver, not a wrapper, so I moved on .The design process is a long-drawn out one for me, because I see so many possibilities and I can't make up my mind. I started this about six months ago, and it will be on-going until I cut off the last piece from the last warp. From selecting the yarns for the first warp, deciding on the placement and proportion of the colors, and calculating the number of threads in each color took me approximately an half of an afternoon.

I'm an Old Timer Now

Remember Dan the Camera Man? We had another opportunity to get our work photographed by him today. Now that I'm so experienced in this process, I just gave him my shawls and scarves and left him to it, which in retrospect was such a waste of valuable learning opportunity. But I did get a few shots of Dan arranging Sue Broad's hand-painted silk fabric.

Remember Dan the Camera Man? We had another opportunity to get our work photographed by him today. Now that I'm so experienced in this process, I just gave him my shawls and scarves and left him to it, which in retrospect was such a waste of valuable learning opportunity. But I did get a few shots of Dan arranging Sue Broad's hand-painted silk fabric.Sue is an experienced weaver who has recently moved to Nelson. How lucky am I to be able to access her wealth of knowledge now! This is only her debut in "Unravelling"; she will be making many return appearances here in the future, I hope.

2006/12/05

Making of an Exhibit - Part 3: Angst and Joy

Monday night, I was weaving an ordered scarf unrelated to the Exhibit(ion); it's a simple Dornick twill in two grays, each strip four-ends wide, the twill direction changing with the color change; the weft is a dirty yellow; all in 100% cashmere. It's the kind of textile I weave often, and what I like to weave. It's guaranteed to have a luxurious hand; the wearer will enjoy it for several years; the construction is sound. And I was weaving on the smaller, four-shaft Jack loom, in the shadow of the big loom on which I have been weaving the Exhibit(ion) pieces.

I was thinking if I had many shawls of the kind I like to weave or am good at weaving, "MY" kind of weaving, the Exhibit(ion) will be filled with reliable but predictable textile, just like a department store. And then I wondered why on earth I ever committed to doing an Exhibit(ion), and knew that I am really the wrong type of person for it. If I need to put myself in a box, I aspire to be a master craftsperson, rather than an artist; I do not aspire to shock or protest or really even express by what I make, but I aspire to weave what is beautiful and functional, and make one person happy. So what I am I thinking, flirting with the idea that what I weave, and a whole bunch of them all lined up, may be interesting to look at, and be worth someone else's time!!

There must be a 6- or 10- or 12-states of emotions artists go through in preparing for their first Exhibit(ion), NOT that I'm calling myself an artist now, but Monday was definitely an "Angst & Self Doubt" stage for me. And it brought back the age-old question of art vs craft to the surface.

Oh, but this little scarf is delicious; and it took only a couple of hours to weave. Darn, I'm good.

I was thinking if I had many shawls of the kind I like to weave or am good at weaving, "MY" kind of weaving, the Exhibit(ion) will be filled with reliable but predictable textile, just like a department store. And then I wondered why on earth I ever committed to doing an Exhibit(ion), and knew that I am really the wrong type of person for it. If I need to put myself in a box, I aspire to be a master craftsperson, rather than an artist; I do not aspire to shock or protest or really even express by what I make, but I aspire to weave what is beautiful and functional, and make one person happy. So what I am I thinking, flirting with the idea that what I weave, and a whole bunch of them all lined up, may be interesting to look at, and be worth someone else's time!!

There must be a 6- or 10- or 12-states of emotions artists go through in preparing for their first Exhibit(ion), NOT that I'm calling myself an artist now, but Monday was definitely an "Angst & Self Doubt" stage for me. And it brought back the age-old question of art vs craft to the surface.

Oh, but this little scarf is delicious; and it took only a couple of hours to weave. Darn, I'm good.

2006/12/01

Making of an Exhibit - Part 2: Exhibit(ion) Shawls, My Shawls

Preparation is time-consuming; weaving is quick. After much thinking and worrying and finally getting a warp on the big loom, I completed two shawls in three days, neither of which I am crazy about. And I have been wondering why I am so tired and so grouchy.

Preparation is time-consuming; weaving is quick. After much thinking and worrying and finally getting a warp on the big loom, I completed two shawls in three days, neither of which I am crazy about. And I have been wondering why I am so tired and so grouchy.Since I signed up to do an exhibit(ion), I've been thinking a lot of about the visual coherence of an exhibit. Since Randall Darwall's workshop, I've been obsessed with color changes and Fibonacci sequence. Since I named the exhibit(ion), I've been concentrating on "Sea, Sand and Sky" expressed in colors, textures and weave structures. And I've been in a rush to try to weave to a schedule.

Fundamentally, the kind of shawls I like to weave haven't got a lot of colors but more like nuances: I use the subtle differences of the color or sheen in the warp and weft to highlight the weave. And these two pieces I've finished don't do that. In fact, rather than spending time to design a twill to show waves and water and sand and grass on the dunes, I'm downloading handsome weaves and sampling them one by one. I've been working with concepts trying to make pictures and not doing "my" weaving. At this rate, I won't be showing my best stuff.

On the other hand, these two suit the theme and make good fillers, and by that I don't mean these are inferior, just not to my liking. I know it's good to extend oneself, and I am doing just that. And in the end, I can never tell what you like.

So for the next one or two warps, I'm going to use one color in the warp and do my thing with weave structures, and get it out of my system. At the end of this process, I should have accumulated about half a dozen, at which time I can decide if I need more of "my" kind of shawls, or the "conceptual/pictorial" kind, or if I have the energy and guts and time to try to combine both.

Thank you for clarifying that for me; you've been of great help.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)